Introduction

Discussed in Topic 1 of this Handbook, mixed methods research is less about the individual qualitative and quantitative research methods you use, and more about how your two methods work together. With that in mind, there are several properties to consider before starting your mixed methods study.

Covered in depth below, there are many mixed methods properties to know and consider when designing this kind of study. These properties are the mixed methods study alignment, the type of integration connecting the qualitative and quantitative components (along with the number of strands, the data priority, and the mixed research questions), and the type of mixed sampling used. For you, each property represents an active decision. Which method takes priority? When do you use which method and why?

Most importantly, the properties (and your subsequent decisions) are all interconnected. They’re numbered to make it easier to reference within Fruitful, but in practice, you make these decisions in a non-linear manner. Also, you’ll find that making a decision for one property can expand or limit possible decisions for other properties. With experience, you’ll get better at designing the most effective mixed study possible.

Typically, the alignment, integration points, and mixed sampling drive the majority of your decisions when planning a mixed methods study. However, understanding each property allows you to make better decisions in novel situations and explain/defend the study design to resistant or skeptical stakeholders.

Let’s work through each of the mixed methods properties to make that journey easier.

Property 1: Mixed Study Alignment

Most of your studies are planned and carefully executed around one single research method. You make a research plan and align on it with your stakeholders. But with a mixed methods study, you might need to use a second method even if you didn’t get alignment and resources beforehand.

Known as an emergent or opportunistic mixed methods study, you might recognize how useful an additional, unplanned method might help address newer, unexpected research questions. Or you might recognize the need to validate or quantify things you’ve learned. This is a great way to add more research to how your stakeholders work and build products. While opportunistic, you might find this type of study challenging to manage, especially when you didn’t collect specific data during the first method that you might need for the second.

An unplanned mixed methods study is when you recognize the value of collecting complementary qualitative/quantitative data only after a study ends.

A planned mixed methods study means you have more time to think through how you’ll use both methods. You can review each of the mixed methods properties, understand the intended outcomes for the research, and design the most effective study possible. Unlike an opportunistic mixed methods study, a planned study offers you more control and strategy.

On the downside, a planned study might need to be drastically modified if the first method produces unexpected, alarming, or irrelevant findings. Your stakeholders will need to be re-aligned as you make necessary changes, extending your study timeline. Keep in mind, that planning doesn’t mean both methods are used back-to-back. While it’s not common, you could design a planned mixed method with days, weeks, or even months before the second method is used.

For example, you might run interviews to help design a survey that measures “customer happiness”. This survey will need to be created, approved, and sent out before data is collected, analyzed, and integrated. In some businesses, it can take several weeks to approve even a short survey. In such cases, it’s common for UX researchers to work on other studies or projects before the second method is used.

When you first start trying a mixed methods approach, you might only be able to run opportunistic studies. That’s okay! If you can increase your comfort and efficiency with individual qualitative and quantitative methods, when the time comes, you should be able to attempt a mixed methods study and deliver meaningful results. Like with other research skills, you’ll get better at recognizing and capitalizing on emergent or opportunistic mixed methods problems or projects.

Regardless of any planned or opportunistic alignment, at some point, your qualitative and quantitative data need to come together. This is known as integration.

Property 2: Integration

Interestingly, the “mixed” in mixed methods research doesn’t refer to the different qualitative and quantitative methods. You can run any study using both a qualitative and quantitative research method, but it doesn’t mean you’re conducting mixed methods research. The mixed, in fact, refers to the interaction or integration between and because of the two methods.

Integration asks you: “Why do you want qualitative and quantitative elements in one study?”

Integration (or integration point) is a reason, decision or moment during the mixed methods study where the qualitative and quantitative components or elements directly influence each other. You can’t make a decision for the quantitative data without also making an interrelated decision for the qualitative data. For one example, you couldn’t plan to collect closed-ended survey data (quantitative) effectively without also figuring why, when, and how to ask open-ended survey items to collect qualitative data. They work hand-in-hand.

Fundamentally, integration forces you to answer the question: “Why do you want a qualitative and quantitative component or element in one study?” If you can’t confidently answer that question, you’re should run a multi-method study with different research methods or be better off taking a mono-method approach instead.

Research elements or components are the various decisions and requirements that work together to become your research study design. Elements include the study’s purpose, MIP definition, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and even the final output or deliverable. You can read more here.

Connecting is also a type of integration, where the qualitative and quantitative data are collected from one sampling frame (like using a survey and then interviewing some survey respondents after). Connecting is not covered in the Fruitful library as its own type of integration because UX researchers often only collect mixed data from one sampling frame, because of time and budget constraints. Put another way, most of your mixed methods studies might use connecting integration simply because of your lack of resources. You can read more about connecting integration here in this article (on the bottom of page 2139).

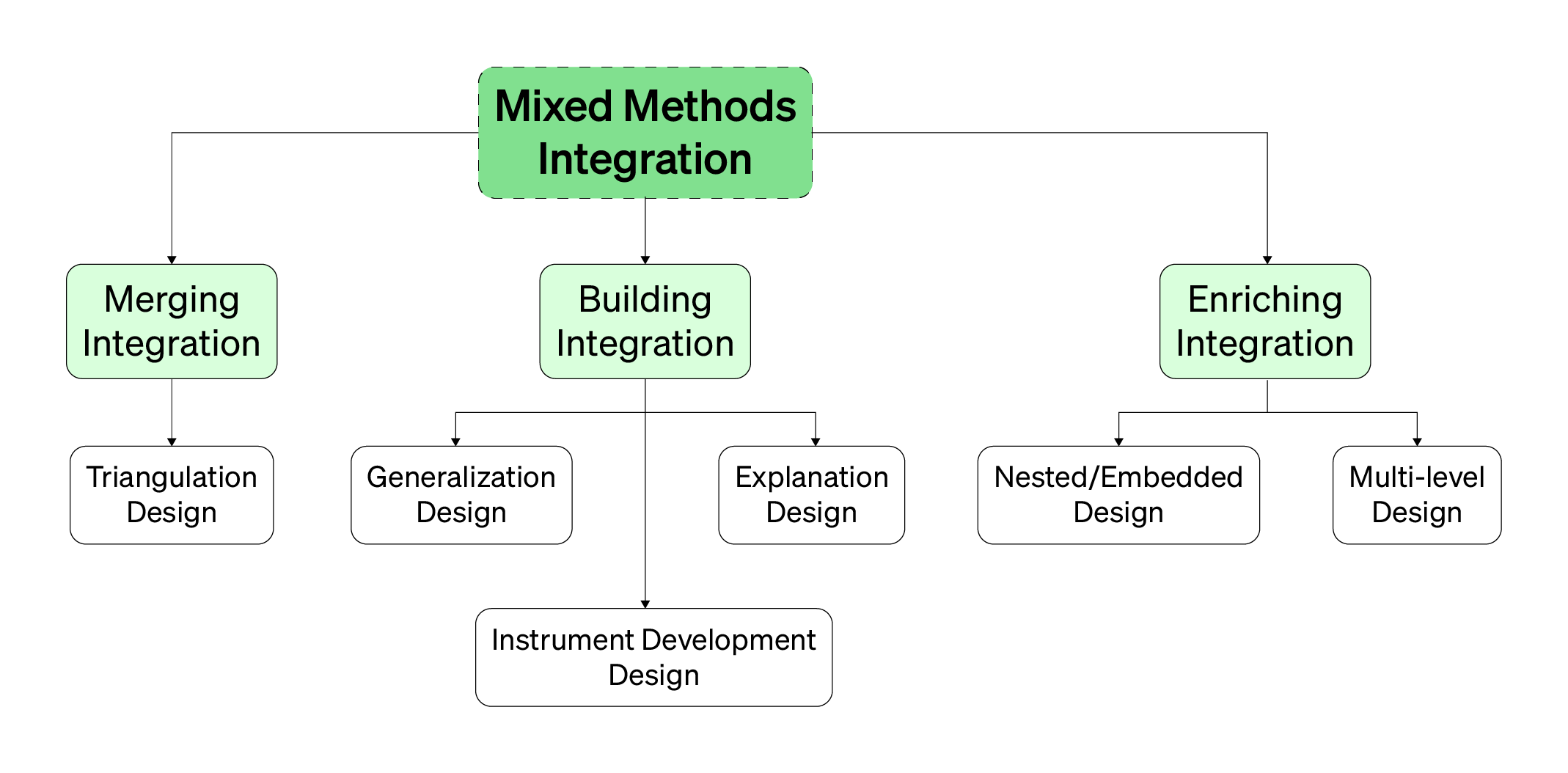

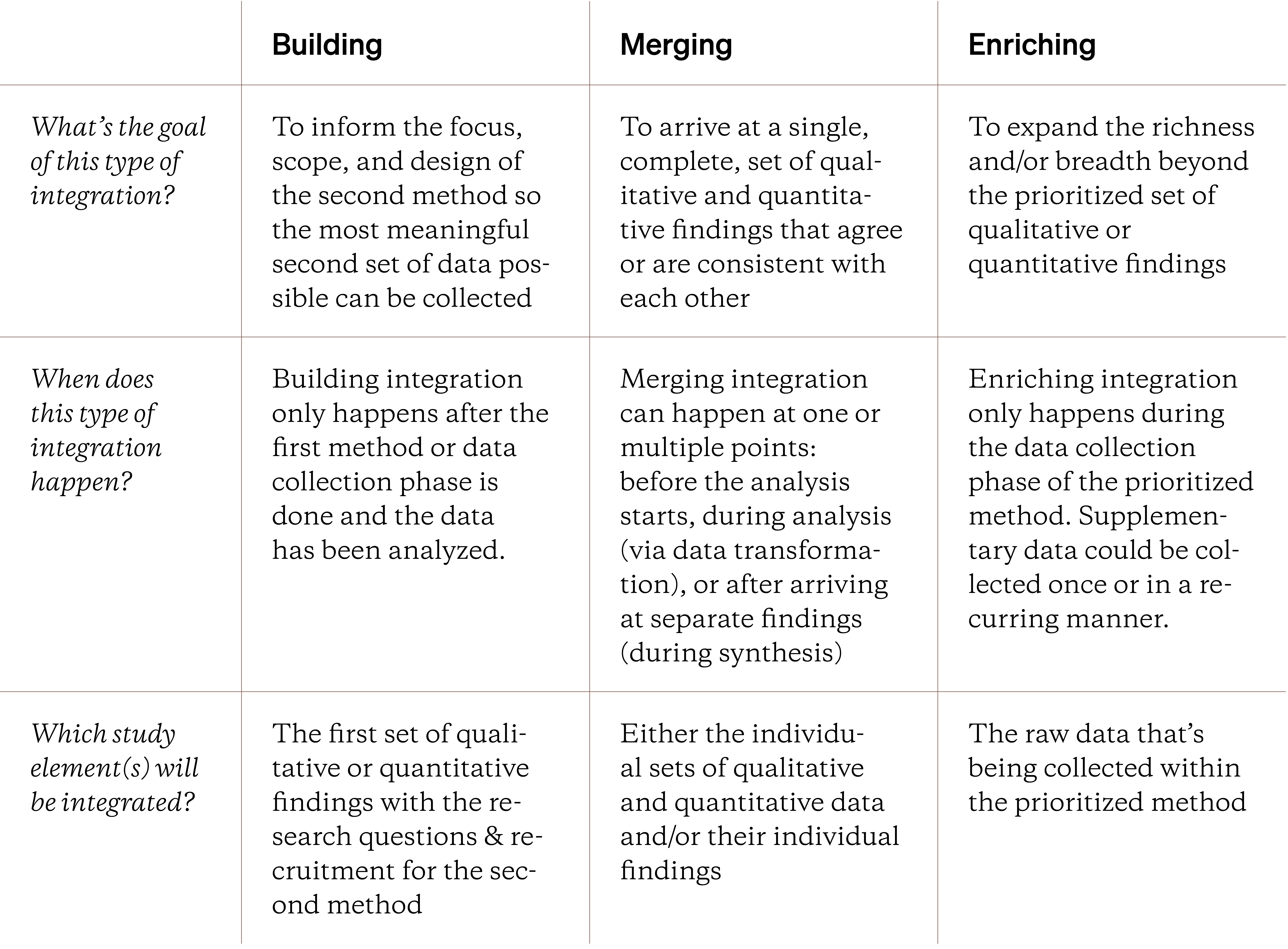

There are three popular answers to this “Why?” question: you want to merge together, build with, or enrich both the qualitative and quantitative elements (as shown in the diagram above). Let’s review these three integration types so you can recognize which type works best for your needs. First, merging integration.

Merging integration is possibly the easiest to understand but least utilized by UX researchers today. You merge both qualitative and quantitative elements to arrive at one set of consistent findings. You answer one set of research questions, with mixed data, to arrive at one set of consistent findings. Both sets of qualitative and quantitative findings should essentially be saying the same thing. For example, a survey with employees on work-life balance and interviews on the same topic should lead to similar, consistent findings. The focus is on the individual findings, not the data or methods.

Merging integration uses both the qualitative and quantitative elements to arrive at the same or consistent findings .

Typically, you’ll find that stakeholders aren’t interested in merging integration or collecting two sets of data (potentially from two samples) to answer the same questions. To them, merging can feel redundant and overpowered, especially when businesses move fast to release products. In these cases, your stakeholders might benefit from building integration.

In practice, merging integration doesn’t always lead to consistent findings. You can read more about why that’s not a bad thing in Topic 5 in this current Handbook.

Building integration is when the qualitative and quantitative elements work together, not against each other. You can think of it like two superheroes teaming up to defeat a tough villain. They might have different powers and weaknesses, but they’re working with each other to stop the same bad guy. There are three subtypes of building integration, that describe how both elements work together: they generalize qualitative findings, they develop a survey using qualitative findings, or they help explain quantitative findings.

Building integration uses one qualitative/quantitative element to inform, guide, or narrow the second element, to answer related or extended research questions.

Building integration requires that you use one method first, analyze its data, and use its findings to influence the second method. UX researchers tend to use building integration most often because they can address different needs and lead to a deeper understanding of the research questions.

The Fruitful research library uses these different names for integrating as a simpler way to refer to popular mixed methods study designs. You can read more about each design in Topic 3 and Topic 4 in the current Handbook.

The last type of integration is known as enriching integration. Here, the focus is on the qualitative and quantitative data together, and not necessarily the methods or findings. While building integration leads to more of an equal relationship between the elements, enriching integration requires that one set of data takes priority over the other. For enriching integration, you typically collect the non-prioritized data during or while collecting the prioritized data.

Enriching integration collects complementary or related qualitative/quantitative data within or during a prioritized method, to better understand the findings from that prioritized method.

One popular way to use enriching integration is by running an experiment (to collect prioritized, quantitative data) while having participants answer some open-ended questions (to collect non-prioritized qualitative data) before, during, and after the experiment. You could then use the qualitative data to better understand or explain the experiment’s quantitative results. Other common approaches include asking closed-ended items during prioritized, qualitative interviews or by nesting meaningful open-ended items within a prioritized closed-ended (quantitative) survey.

The table below summarizes these three types of integration.

One important thing to recognize is that many mixed method studies have multiple types and points of integration. You might reuse the same sample to collect both sets of data or you might use enriching integration for specific topics within a larger, building integration mixed methods study. It’s all up to you to decide the type and number of integration points there’ll be based on your study goals and constraints.

A mixed method study might have multiple types and points of integration; it’s up to you to decide the type and points of mixed methods integration necessary for your study.

Integration tends to be the most influential property when designing a mixed study. If you can figure out what type(s) and point(s) of integration you need, planning the rest of the study becomes easier because certain options and choices can be immediately removed. You can also know data priority and the number of strands (or timing) for your study. Let’s review these two other properties next, starting with research strands.

Property 3: Timing (or Strand)

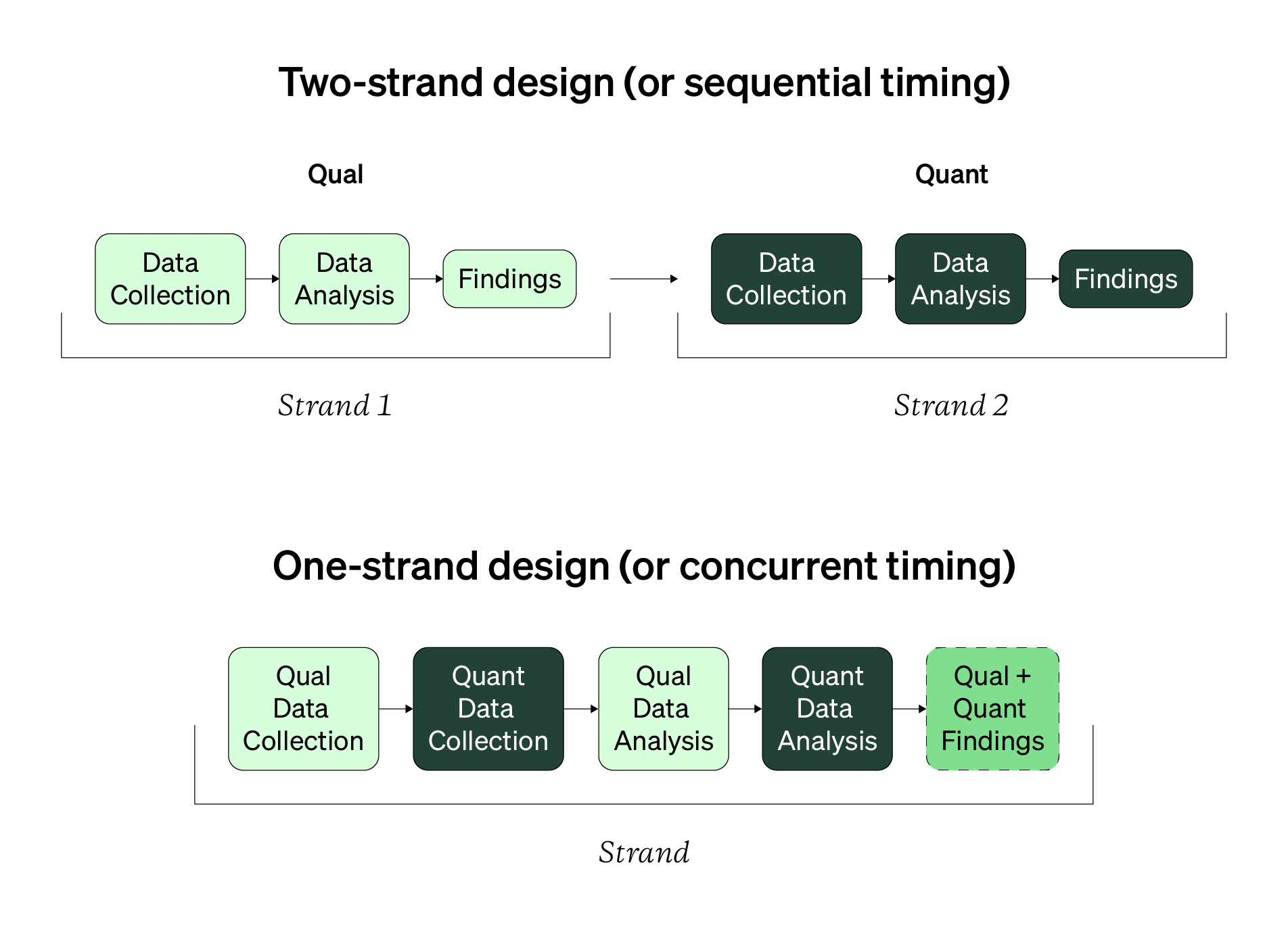

Timing is about when you’ll collect qualitative and quantitative data within a mixed methods study. In accessible mixed methods literature online, you might see terms like “sequential” or “concurrent” timing. However, this language can hide the fact that time passes between qualitative and quantitative data collection. For example, concurrent timing doesn’t mean that both sets of data are collected at the same time, but that both sets of data are collected before the data analysis phase.

Terms like “sequential” or “concurrent” timing simplify when qualitative & quantitative data collection happens in a mixed methods study.

To make this easier to understand, it’s easier to use the term strand when discussing mixed methods timing. Below is an excerpt from a 2009 book by Abbas Tashakkori & Charles Teddlie, two mixed methods research pioneers, that describes what a research strand is.

A strand is a component of a study that encompasses the basic process of conducting quantitative or qualitative research: posing a question, collecting data, analyzing data, and interpreting results based on that data ("Foundations of Mixed Methods Research", Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009).

In simpler language, a strand is a distinct phase of research that goes from data collection, data analysis, and data synthesis and interpretation. Explored further in Topic 3, a connecting mixed methods study design has two research strands, while a merging mixed methods design has only one strand.

Above is a diagram to help you understand timing and strands better. If you wait to analyze both sets of data, you’re likely designing one strand (or concurrent timing) mixed methods study; if you analyze one set of data and then use it to inform how you’ll collect the other set of qualitative/quantitative data, then your mixed methods study has two strands (sequential timing).

In the diagram above, the one stand (concurrent timing) study below shows that you’re not collecting qualitative and quantitative data at literally the same time, just that you’re collecting it before you do both sets of analysis. You can read more about strands here, starting on page 63. Below is a table describing one and two-strand designs for easy reference.

Research strand and research phase are sometimes used interchangeably across mixed methods literature.

You can also have multiphase mixed methods designs, where one or more strands happen sequentially while other strands happen concurrently. Multi-phase mixed designs take longer and are more complex to run, but they offer you the best of both worlds. You can read more about multiphase designs here on page 72.

Regardless of the timing of data collection, there’s a big limiting factor: you. You can only analyze so much data and still meet timelines. Even worse, you can only analyze one set of data at a time. Even if collect both sets of data before analysis, you’ll still have to analyze one data set and then the other, or switch regularly between both sets. You get faster data collection with a one-strand design, but with short timelines, you’ll be forced to rush through both individual datasets and the integrated (mixed) dataset. This can lead to careless mistakes during analysis and missed opportunities or patterns. On the other hand, a two-strand, sequential study allows you time for deeper, less error-ridden analysis. But your stakeholders likely won’t appreciate the longer study timeline.

Regardless of timing or strand, you can only analyze your data in a linear fashion.

As you might expect, the more strands you have, the longer and more complex your study will be. When you first start out, it might be best to focus on two-strand mixed designs (sequential timing) because you can dedicate more focus to each individual strand.

Property 4: Data Priority

The next property is priority or sometimes referred to as dominance in mixed methods literature. Priority means giving one set of data or method more focus, emphasis, or importance over the other. For example, if you had a lot of qualitative research questions and wanted to quantify any resulting qualitative themes, you might treat interviews as the prioritized or dominant method. This means you’ll spend more time analyzing and understanding the qualitative interview data than the follow-up quantitative survey data.

Priority means which method or set of data is more important or meaningful to collect, analyze, and report on.

While common, you don’t need to specify a dominant method. If you gave equal status or weight to both methods, you’ll be giving the same amount of detail and focus to both the qualitative and quantitative data sets. Having a dominant method might be better for a two-strand mixed design (sequential timing) while giving both methods equal weight can be better for a one-strand design (concurrent timing). And typically, mixed methods studies that use merging integration tend to give equal priority to both sets of data, while enriching and building integration studies have a clear qualitative or quantitative data priority.

The best way to recognize which method or dataset will be given priority is to look at your research questions and the data you’ll need to address them. Asking yourself “What’s the most important qualitative and/or quantitative data you need to collect?” can help you decide on data priority. For quick reference, quantitative data needs tend to be descriptive, comparative, correlational, and experimental, while qualitative data needs tend to be dynamic, open-ended, and unstructured.

Sometimes, however, you might give priority to one method or dataset based on factors outside of your research questions or data needs. For example, you might give priority to a qualitative method because you might struggle to run quantitative research at scale.

Other times, you might give priority based on your experience — or inexperience! — with a particular type of research or method. Or you might give priority to one method or dataset based on your stakeholders’ requests or frustrations. Your stakeholders might overvalue quantitative data and make it the priority (in this case, you might look to collect non-priority qualitative data to balance, connect, or enrich the prioritized quantitative data).

Finally, let’s look at the last property covered here: mixed sampling or how you’ll collect both sets of data from participants.

Property 5: Mixed Sampling

When you design a study around one method, the standard advice is to use sampling associated with that method. For example, interviews are a qualitative research method, so it'd be best to use qualitative, non-random sampling techniques when recruiting participants. But how should you recruit participants if you have a qualitative and a quantitative research method in one study?

The table below describes different sampling approaches you could take in a mixed methods study you design. Let’s review each type of sampling, starting with parallel sampling.

Parallel sampling is when you two samples with the same Most Informative Participant (MIP) definition. From each sample, you collect one set of qualitative or quantitative data.

Parallel mixed sampling

Parallel mixed methods sampling is essentially running two independent studies at one time. While this seems easy, you might struggle to get participants who fit your MIP definition and meet both your qualitative and quantitative sample size requirements. For example, you might be able to schedule 12 interviews with customers but only get 40 survey responses. Sampling and recruiting in a parallel manner works best for triangulation and generalization mixed methods designs.

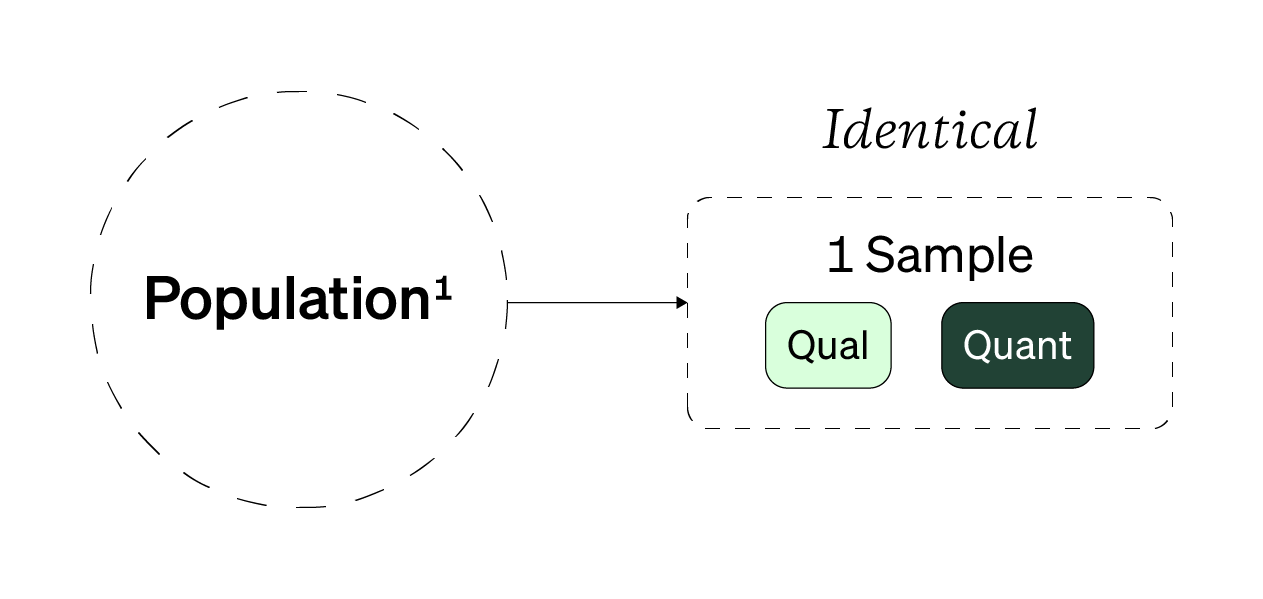

Identical mixed sampling

If you can’t manage the cost and time of two samples, you could take an identical sampling approach. Here, you have only sample but collect both qualitative and quantitative data from this one set of participants.

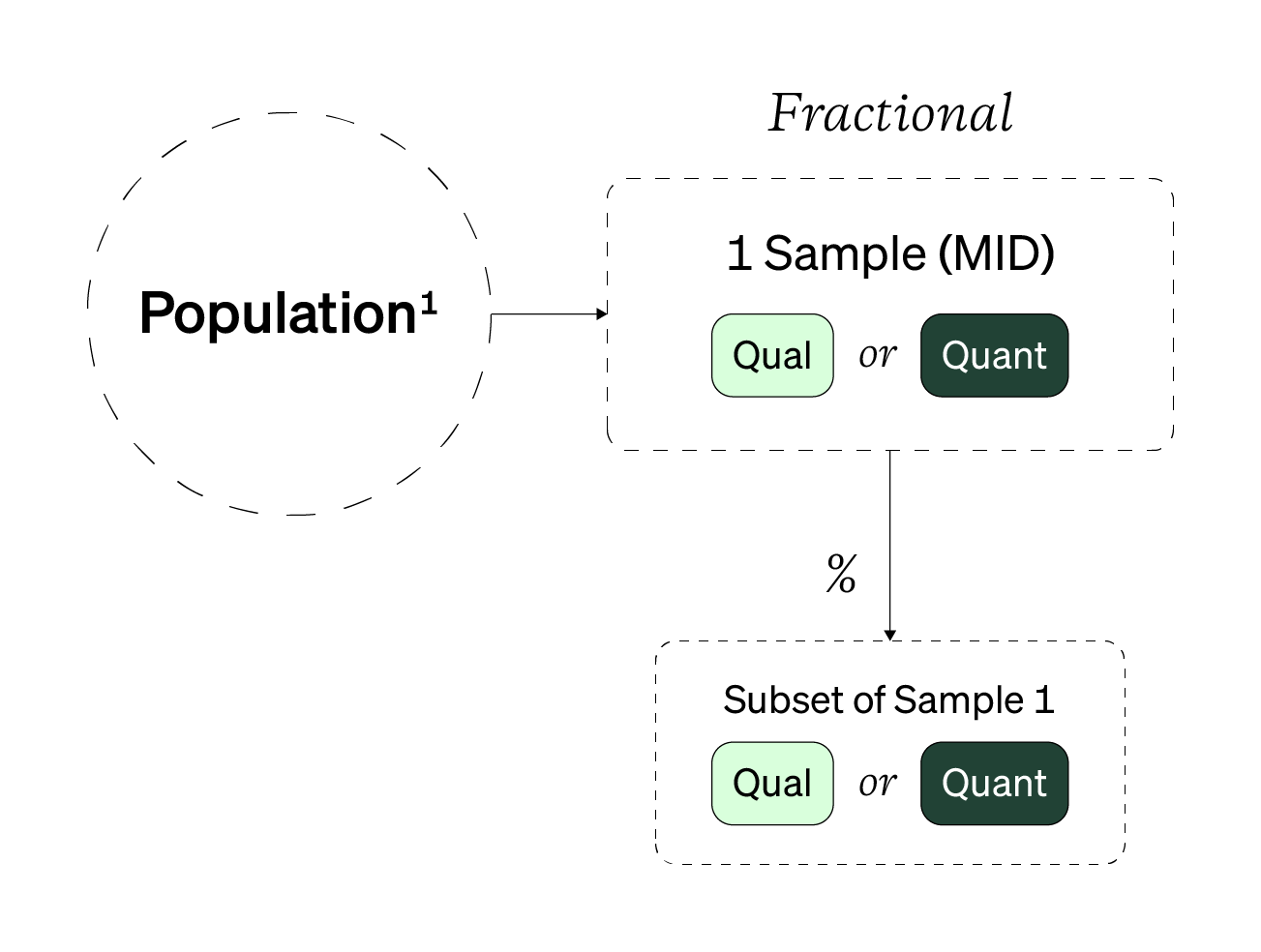

Fractional mixed sampling

You could consider a fractional sampling approach. You take one sample (ideally as large as you can manage) and collect either qualitative/quantitative data. Then, you select and study a relevant subset for the other set of qualitative/quantitative data.

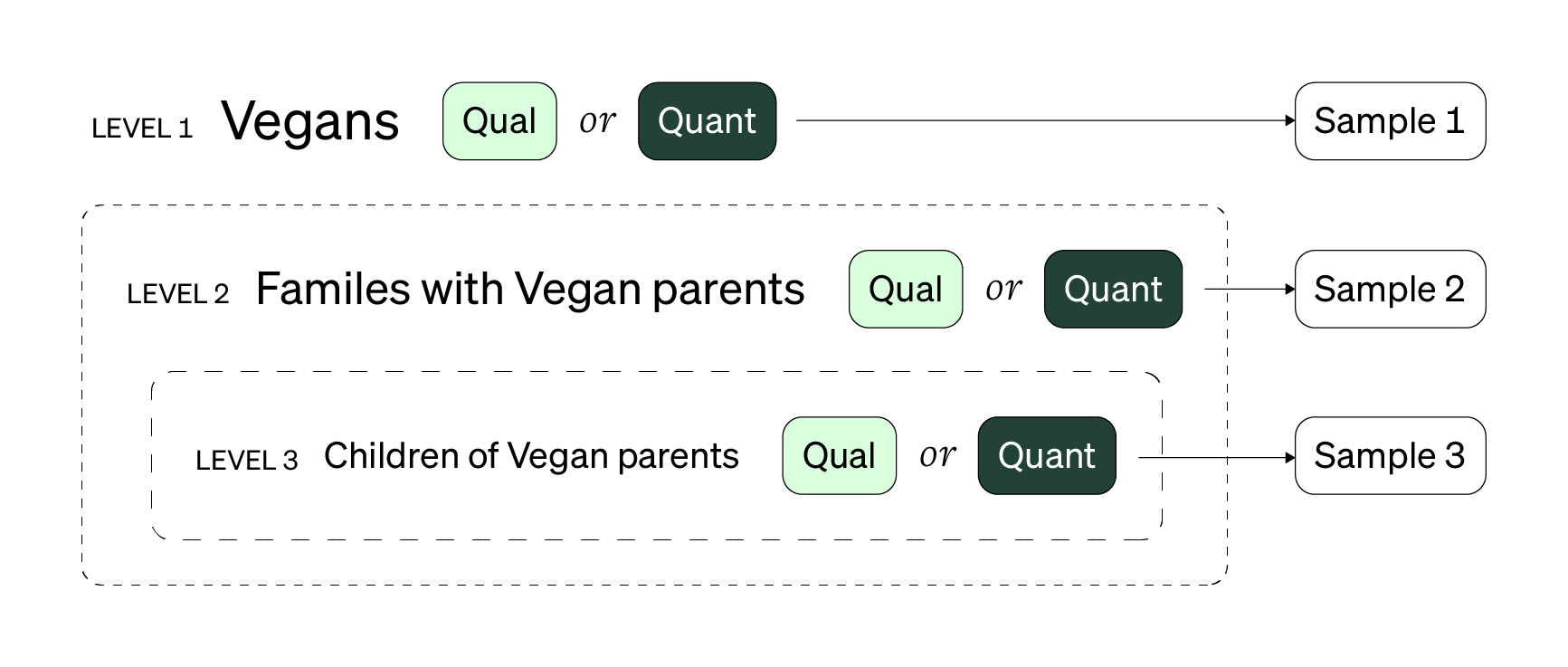

For an example of multi-level sampling, let’s pretend that the population you want to understand are vegans. You could have three different levels, as shown in the diagram below. You could start by looking at quantitative data at the national level for vegans. Then you could have the next level be collecting qualitative or quantitative data from families where the parents are both vegan. Finally, you could collect qualitative or quantitative data from children who’s parents are both vegans.

For another example, you could study how district/regional managers (level 1), store managers (level 2), and store employees (level 3) all use their company-provided smartphones for store-to-store communication.

The aim with multilevel mixed sampling is to understand how being in a particular subgroup influences the qualitative, quantitative, and mixed findings.

In a multi-level study, you could collect qualitative or quantitative data from all of the levels. However, it’s common to have the first level be large-scale quantitative data and the subsequent levels be qualitative due to the ease of data collection and focus. You can read more about multi-level mixed methods studies in Topic 4 of this Handbook.

You have to decide which type of mixed sampling is appropriate for your study. If you’re short on time, an identical sampling approach is best because you maximize learning from one sample. If you need flexibility, take a fractional approach. If you have multiple sub-groups to understand, consider a multi-level approach. And if you have time and reliable recruitment, consider a parallel approach. You can think of the parallel approach as the “gold standard” mixed sampling as it reduces any bias from one set of collected data to the next.

Pick a mixed sampling approach that address your mixed design needs and allows you to maximize your limited recruitment resources.

Also consider the practical and tangible effort needed to recruit participants. With an identical mixed sampling approach, you only need to create one screener. With a parallel approach, you’ll might have to manually schedule for moderated qualitative sessions and ensure any unmoderated quantitative methods are working properly.

If you take a multi-level approach, you might need different types and amount of study compensation (such as offering more for a manager interview over an employee interview). If you take a fractional approach, you might lengthen study timelines so the most informative participants can provide data again given their schedules.

For more help on recruitment, check out this Handbook on participant recruitment.

To get comfortable with mixed methods research and its sampling needs, an identical or fractional approach is best. It allows you to either focus on maximizing one sample or afford you flexibility and a chance to learn from the set of data to make smarter sampling and study decisions for the second.

Closing Thoughts

This is one of the longest Topics in the entire Fruitful research library. From alignment to integration, sampling to timing, there are a lot of decisions you’ll have to make to run even one mixed methods study. Instead of being overwhelmed, you can reframe these many properties as offering you flexibility. If you can’t use that kind of integration, use another one. If you can’t have two samples, shift your focus to collecting both sets of data from one, larger sample.

Luckily, very talented and prolific mixed methods researchers (like Charles Teddlie, Abbas Tashakkori, & John W. Creswell) have taken these properties and generated several mixed designs that you can understand and apply right away. In the next two Topics in this mixed methods research Handbook, let’s look at these designs. To make it easier to absorb (and to continue to use the integration language mentioned at the top), the topics are focused on building integration mixed designs and merging & enriching mixed designs.

- mixed methods data priority

- concurrent & sequential timing

- mixed methods integration; integration point

- building integration; merging integration; enriching integration

- mixed methods parallel sampling; identical sampling; fractional sampling; multi-level sampling

- research strand; research phase

- Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences (paid book)

- Prevalence of Mixed-methods Sampling Designs in Social Science Research (article)

- "A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research" (article)