Your Sample isn't the Population

In the previous Handbook, there were lots of diagrams that described how sampling works. You can't study everyone, so you sample a portion of the population to learn from. And if your sample is representative of the population, you could infer that your results are likely true for the population. For example, if you learned from your representative sample that 80% of respondents hated the latest feature, you could reasonably infer that this similar proportion describes how your population feels too. But there's an issue here.

Unless you study everyone in your population, the findings from your sample will be different than what's true for the population. After all, a sample of 10,000 participants is really powerful for noticing and describing relationships, but it's significantly smaller than a population of one million or more people.

No matter how large your sample is, there'll always be a difference between what you see and what's true at the population level. You can read more this idea here.

There'll always be a difference between your sample findings and what’s true at the population level.

No matter how large your sample is, you’ll never get perfectly accurate results. The goal then isn’t to shoot for the largest sample size but a size that maximizes value without exhausting all of your reasons. You have to know what sample size is large enough.

The Cleanliness Principle

.png)

Let’s start by doing a simple thought experiment: Think about taking a shower. Without too much detail, you use water and soap to get clean. You need a certain amount of each to get an acceptable level of cleanliness. But using more water and more soap doesn't mean you get even cleaner. After some point, not only are you wasting your resources, you’re damaging your body. Up to a certain point, soap and water are a good thing; after that point, they’re wasteful or dangerous.

You can apply this idea to your research. Up to a certain point, there are clear benefits to learning from a larger sample. You can get more precise estimates for patterns, have results be more stable or less volatile, detect very hard-to-notice trends, or even use specific formulas or theorems.

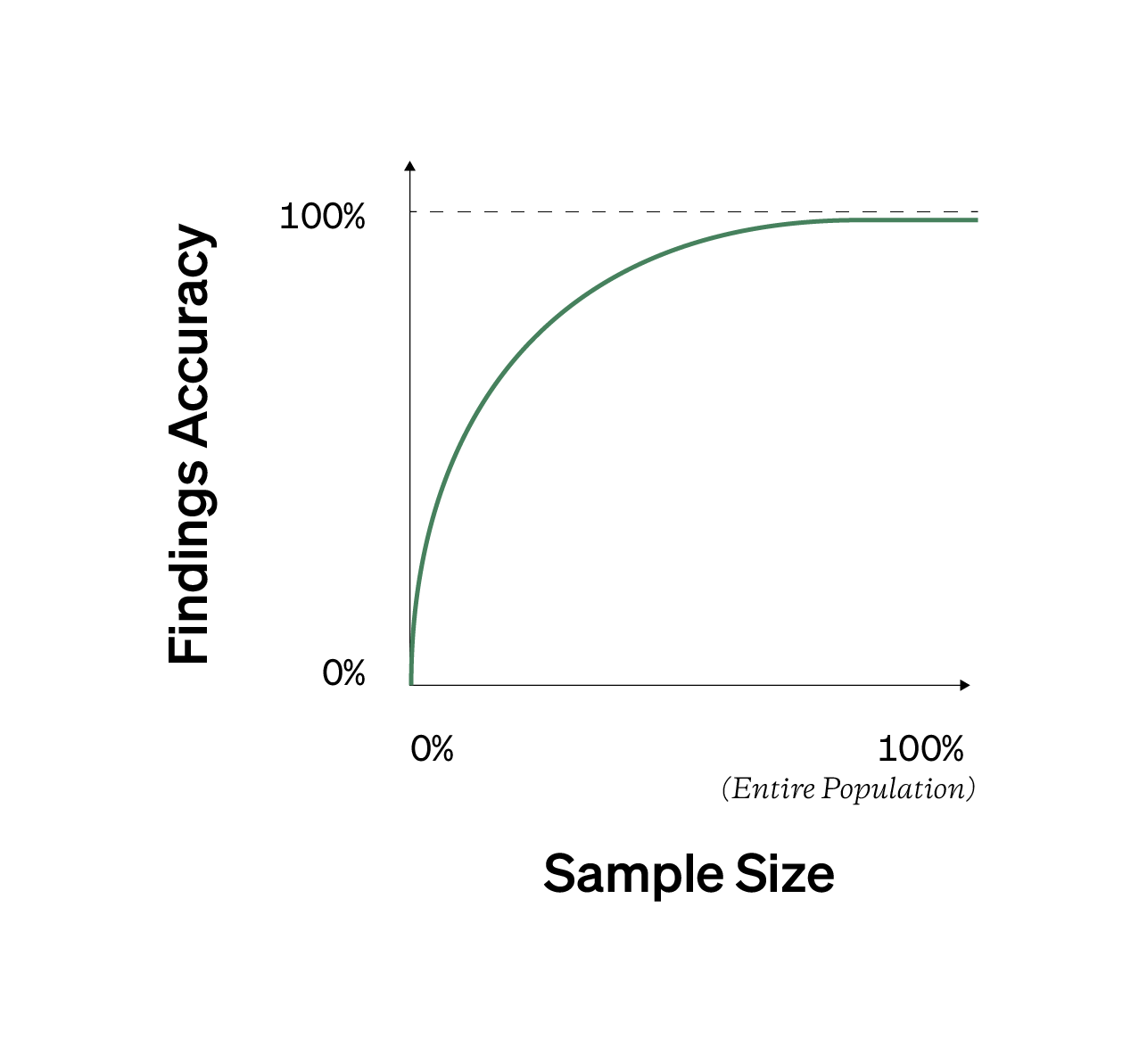

But after a certain point, you’re wasting resources and taking on more risk and cost for your research. Below is a diagram displaying the relationship between the size of your sample and the accuracy or “correctness” of your findings. It’s a theoretical diagram, but the idea behind it is what matters.

When you move from small to large samples, the accuracy of your findings initially shoots up. But as your sample size gets larger, your accuracy increases by smaller amounts. You have to study a lot more people to get slightly more accurate findings. At some point, you'd spend more resources than needed.

The cleanliness principle is built on top of this idea. It asks you to consider three simple questions before shooting for larger sample sizes:

- How “large” is large enough to see value?

- When is the number of participants you have enough to end your research?

- At what point are you wasting time and resources?

If the goal is to learn and more quickly, then a larger sample means you might be spending resources for less learning and longer timelines. The next Topic provides practical sample sizes for qualitative and quantitative research. You use those numbers as a starting point on when to stop collecting more participants.

Unsustainable Sampling

With larger samples, you’re also exhausting your limited sampling frame quickly. You might have to contact three thousand people from your sampling frame to get a sample size of one thousand survey respondents. You also can't contact thousands of people for every study you need to run without spending too many resources or raising too many of your stakeholders’ eyebrows.

In the worst case, you'll run out of people to contact. If your sampling frame gets exhausted, that means you'll be forced to re-contact people. But if you contact people repeatedly, you might signal that research is "annoying", making potential participants ignore or block all your future recruitment efforts.

Delayed Learning

Knowing larger sample sizes take longer to get than small ones is fairly obvious. What's not obvious is your stakeholder’s patience with that longer recruitment time.

When your stakeholders want a “large” sample size, it contradicts their want for “fast research.”

Unless your sampling frame is massive, your stakeholders will have to wait longer to reach a desired, large sample size. They'll also have to wait longer to digest and use your research findings. In simpler terms, your stakeholders wanting a larger sample directly contradicts your stakeholder’s desire to do research quickly.

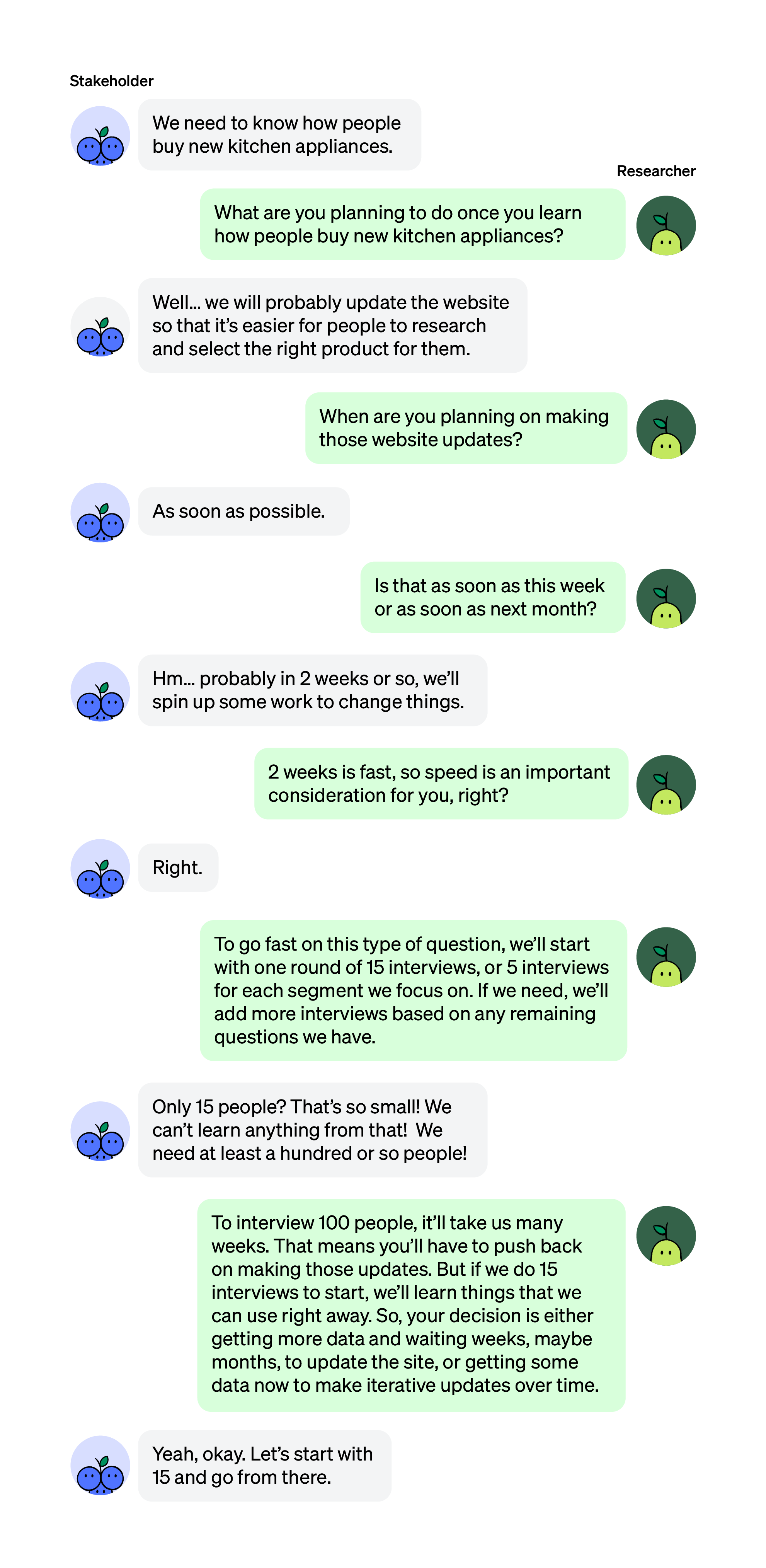

Instead of focusing on size, frame conversations around speed with your stakeholders. Let’s see an example of how to reframe this. Let's pretend you work at a startup making a new type of smart kitchen appliance. Below is a fake conversation with one of your stakeholders who wants a large sample:

In the example conversation, faster learning and product iteration was more valuable than hitting a large sample size goal.

Disrespect & Fatigue (in Qualitative Research)

In the fake conversation above, it might sound outlandish to have a stakeholder ask for 100 interview participants. But you could somewhat unreasonably interview 30 people in a week.

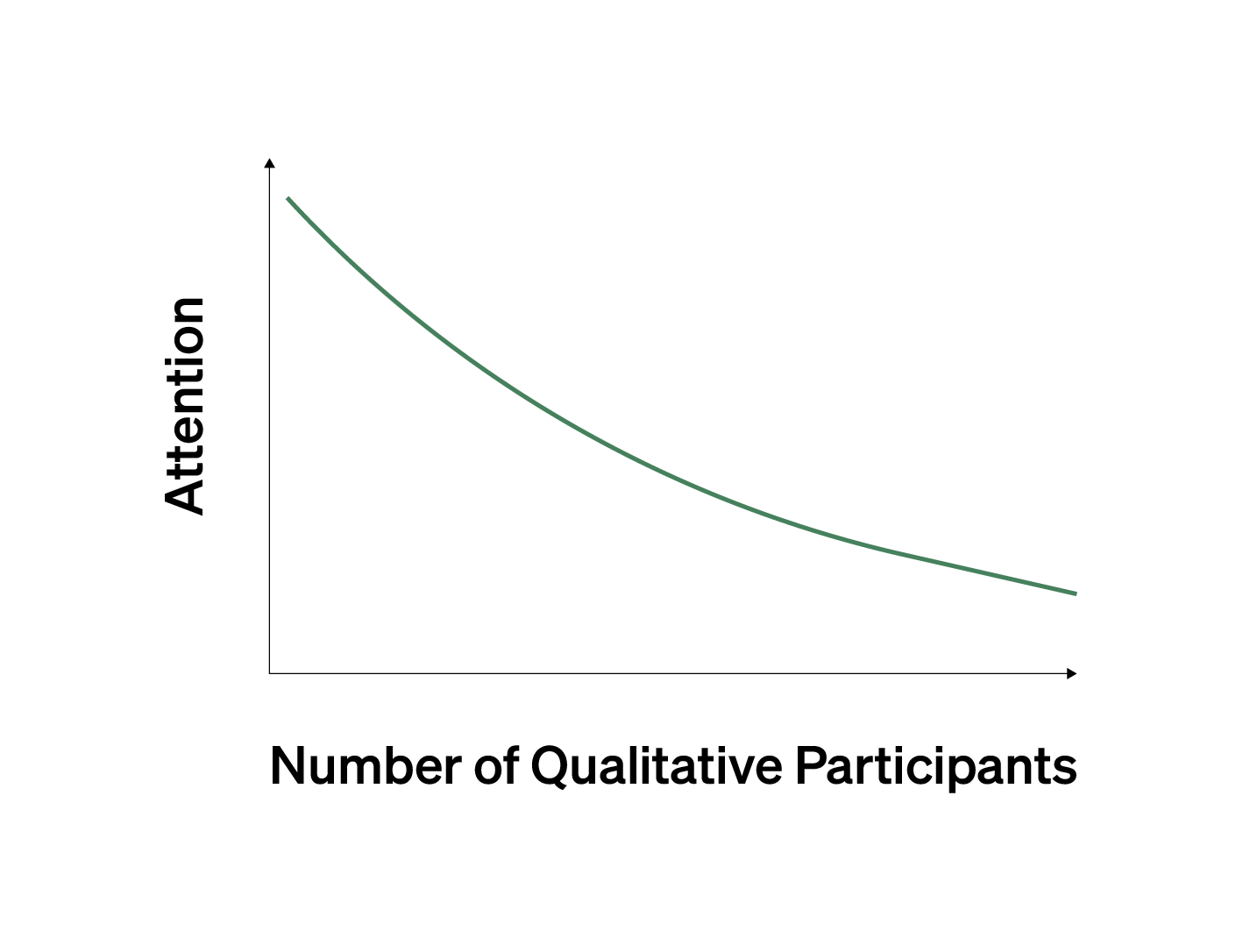

But consider the impact of this larger, qualitative sample size. In the first interview, your energy and attention are high. Your notes are detailed, and your rapport-building is warm and inviting. But what about participant #20? Can you completely focus on this person who's gracious enough to give you their stories, emotions, and time? When you reach participant #30, you're mentally, emotionally, and physically drained.

When this happens, you're not only doing a disservice to your work but being disrespectful to your participants. Before aligning on large qualitative sample sizes, recognize if you can give the necessary amount of attention and energy needed to run meaningful research. If not, focus on breaking up your study into chunks (studying only a handful of questions with a handful of people; repeat) or addressing the demand for larger and larger sample sizes.

A Lot (More) of a Bad Thing

If you’re running convenient or rushed research, a large sample means collecting lots of biased or meaningless data. How you design the study (the topic of the next phase) matters as much as the number of people you learn from. A large sample size can’t overcome the serious issues that plague a biased, inappropriate, lazy, or unintentional study.

A “large” sample size can’t overcome a bad study design.

Large samples do have value. They can help you notice non-obvious patterns and build trust in the research process. But remember, your focus isn't to get the largest number of participants but to do enough that your team sees value in your research. And for them, value is recognized when they can use your research to make more confident decisions. It's up to you to showcase why your research is valuable beyond the sample size.

Nonresponse Bias

Nonresponse bias is one final, unremovable reason not to focus on large samples. There’ll always be some proportion of potential participants that can't or don't always want to take part in your research. Nonresponse bias is hard to predict and avoid. Worse, wanting a larger sample size means dealing with more nonresponse bias. You need to contact many people to get a larger sample size. And that only increases the number of people who choose not to participate.

If you're stuck between a recruitment strategy that gets you a larger sample size or one that gets you lower non-response bias, shoot for the second strategy. You'll learn from otherwise unheard people, making it more likely that you will discover important or easy-to-miss findings.

The ideas, cost, and impact of small and large samples are more nuanced than the numbers that go alongside them. Being able to see into the future and setting yourself up for success while navigating stakeholders away from unreasonable or impractical ideas is a critical skill you’ll have to develop.

But at the end of the day, you’ll have to align on and study some specific number of people. What exactly should those numbers be?

- Nonresponse bias; nonresponse bias analysis

- Participant / study recruitment

- Minimum sample size estimation